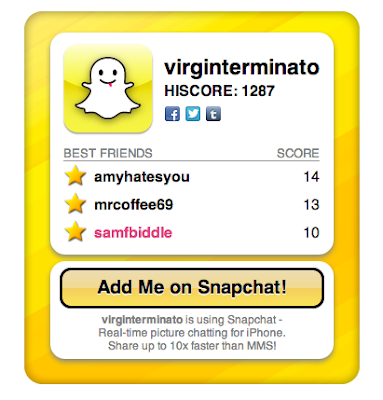

If you and a friend Snap back and forth for consecutive days, you build up a streak which is tracked in your friends list. Young people quickly threw their heart and souls into building and maintaining streaks with their friends. This was literally proof of work as proof of friendship, quantified and tracked.

Streaks, of course, have the wonderful quality of being unbounded. You can maintain as many streaks as you like. If you don't think social capital has value, you've never seen, as I have, a young person sobbing over having to go on vacation without their phone, or to somewhere without cell or wifi access, only to see all their streaks broken. Some kids have resorted, when forced to go abroad on a vacation, to leaving their phone with a friend who helps to keep all the streaks alive, like some sort of social capital babysitter or surrogate.

What's hilarious is how efficiently young people maintain streaks. It's a daily ritual that often consists of just quickly running down your friend list and snapping something random, anything, just to increment the streak count. My nephew often didn’t even bother framing the camera up, most his streak-maintenance snaps were blurry pics of the side of his elbow, half his shoulder, things like that.

Of course, as evidence of the fragility of social capital structures, streaks have started to lose heat. Many younger users of Snapchat no longer bother with them. Maintaining social capital games is always going to be a volatile game, prone to sudden and massive deflationary events, but while they work, they’re a hell of a drug. They also can be useful; for someone Snapping frequently, like all teens do, having a best friends list sorted to the top of your distribution list is a huge time-saver. Social capital and utility often can’t be separated cleanly.

Still, given the precarious nature of status, and given the existence of Instagram which has always been a more unabashed social capital accumulation service, it’s not a bad strategy for Snapchat to push out towards increased utility in messaging instead. The challenge, as anyone competing in the messaging space knows, is that creating any durable utility advantage is brutally hard. In the game theory of tech competition, it's best to assume that any feature that can be copied will. And messaging may never be, from a profit perspective, the most lucrative of businesses.

As a footnote, Snapchat is also playing on the entertainment axis with its Discover pane. Almost all social networks of some scale will play with some mix of social capital, utility, and entertainment, but each chooses how much to emphasize each dimension.

Lengthening the Half-life of Status Games

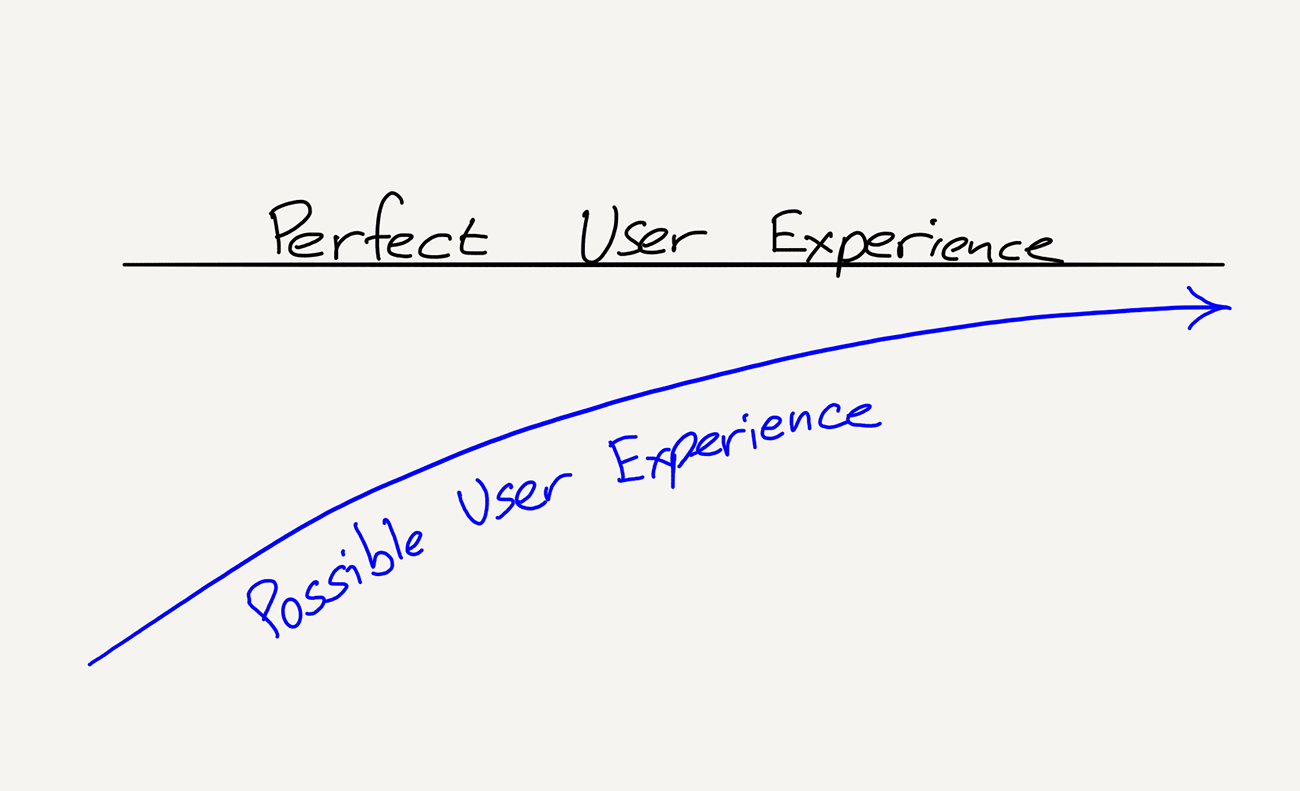

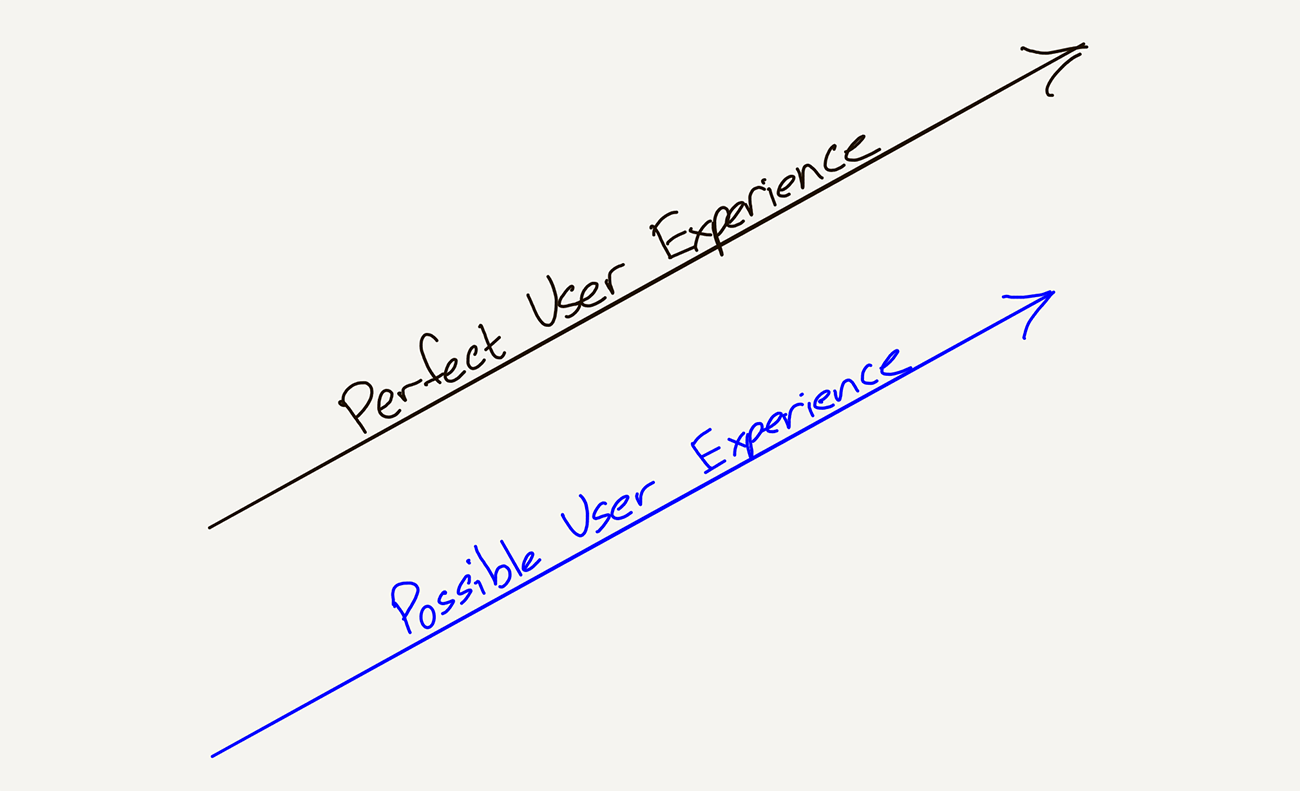

The danger of having a proof of work burden that doesn't change is that eventually, everyone who wants to mine for that social currency will have done so, and most of it will be depleted. At that point, the amount of status-driven potential energy left in the social network flattens. If, at that inflection, the service hasn't made headway in adding a lot of utility, the network can go stale.

One way to combat this, which the largest social networks tend to do better than others, is add new forms of proof of work which effectively create a new reserve of potential social capital for users to chase. Instagram began with square photos and filters; it's since removed the aspect ratio constraint, added video, lengthened video limits, and added formats like Boomerang and Stories. Its parent company, Facebook, arguably has broadened the most of any social network in the world, going from a text-based status update tool for a bunch of Harvard students to a social network with so many formats and options that I can’t keep track of them all. These new hurdles are like downloadable content in video games, new levels to spice up a familiar game.

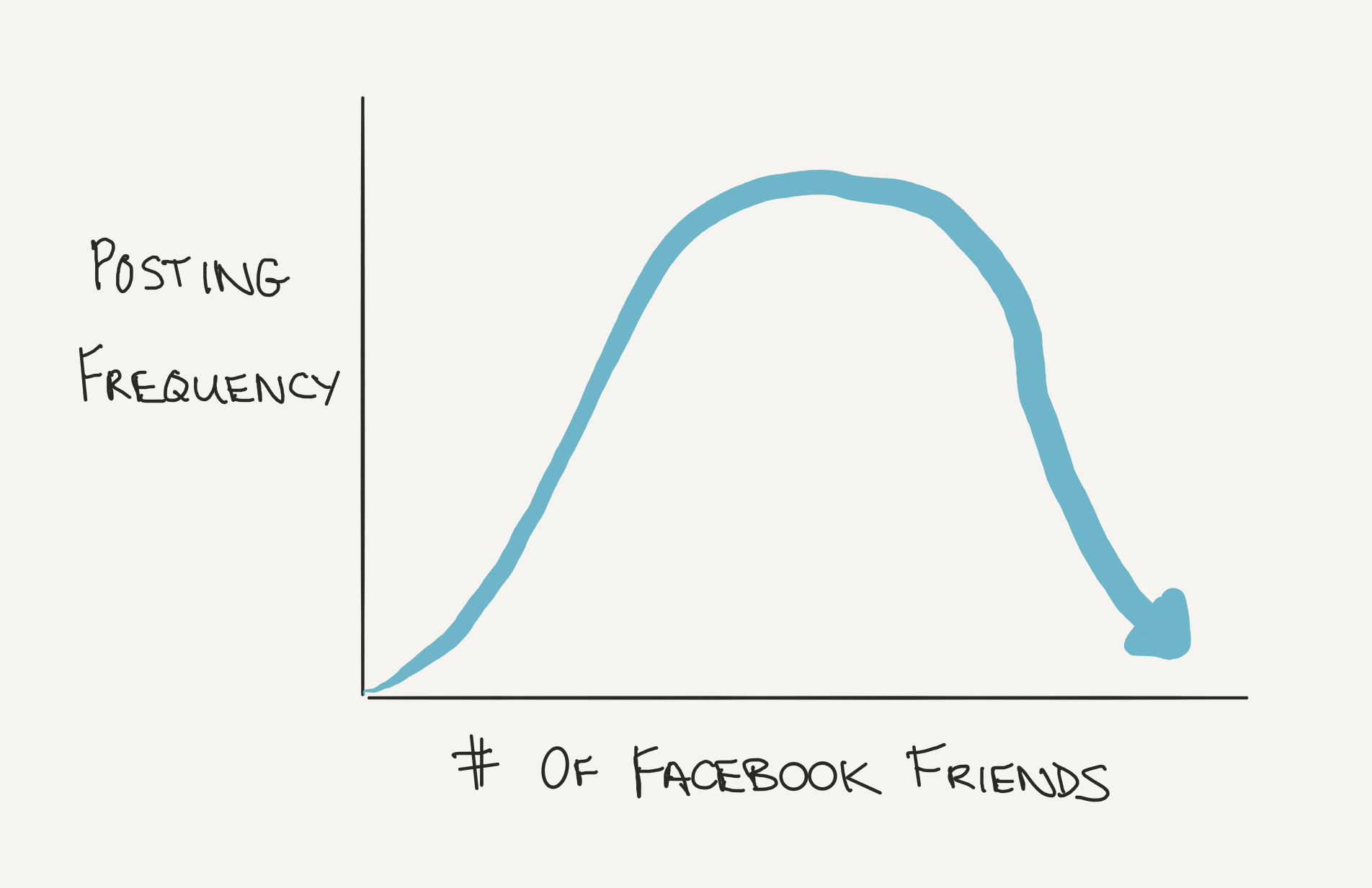

Doing so is a delicate balance, because it’s quite possible that Facebook is so many things to so many people that it isn't really anything to anyone anymore. It is hard to be a club that admits everyone but still wants to offer a coherent status ladder. You can argue Facebook doesn't want to be in the status game, but if so, it had better add a lot more utility.

Video games illuminate the proof of work cycle better than almost any category, it is the drosophila of this type of analysis given its rapid life cycle and overt skill-versus-reward tradeoffs. Why is it, for example, that big hit games tend to have a life cycle of about 18 months?

A new game offers a whole new set of levels and challenges, and players jump into the status competition with gusto. But, eventually, skill differentiation tends to sort the player base cleanly. Players rise to the level of their mastery and plateau. Simultaneously, players become overly familiar with the game's challenges; the dopamine hit of accomplishment dissipates.

A franchise like, say, Call of Duty, learns to manage this cycle by investing hundreds of millions of dollars to issue a new version of the game regularly. Each game offers familiarity but a new set of levels and challenges and environments. It's the circle of life.

Some games can lengthen the cycle. For example, casino games in Vegas pay real money to set an attractive floor on the ROI of playing. Some MMORPGs offer other benefits to players, like a sense of community, which last longer than the pure skill challenge of playing the game. Looking at some of the longer lasting video game franchises like World of Warcraft, League of Legends, and Fortnite reveal a lot about how a parallel industry has succeeded in lengthening the productive middle age of its top properties.

I suspect the frontier of social network strategy will draw more and more upon deep study of these adjacent and much older social capital games. Fashion, video games, religion, and society itself are some of the original Status as a Service businesses.

Why Some Companies Will Always Struggle with Social

Some people find status games distasteful. Despite this, everyone I know is engaged in multiple status games. Some people sneer at people hashtag spamming on Instagram, but then retweet praise on Twitter. Others roll their eyes at photo albums of expensive meals on Facebook but then submit research papers to prestigious journals in the hopes of being published. Parents show off photos of their children performances at recitals, people preen in the mirror while assessing their outfits, employees flex on their peers in meetings, entrepreneurs complain about 30 under 30 lists while wishing to be on them, reporters check the Techmeme leaderboards; life is nothing if not a nested series of status contests.

Have I met a few people in my life who are seemingly above all status games? Yes, but they are so few as to be something akin to miracles, and damn them for making the rest of us feel lousy over our vanity.

The number of people who claim to be above status games exceeds those who actually are. I believe their professed distaste to be genuine, but even if it isn't, the danger of their indignation is that they actually become blind to how their product functions in some ways as Status as a Service business.

Many of our tech giants, in fact, are probably always going to be weak at social absent executive turnover or smart acquisitions. Take Apple, which has actually tried before at building out social features. They built one in music, but it died off quickly. They've tried to add some social features to the photo album on iOS, though every time I've tried them out I end up more bewildered than anything else.

iMessages, Apple fans might proclaim! Hundreds of millions of users, a ton of usage among teens, isn't that proof that Apple can do social? Well, in a sense, but mostly one of utility. Apple's social efforts tend to be social capital barren.

Since Apple positions itself as the leading advocate for user privacy, it will always be constrained on building out social features since many of them trade off against privacy. Not all of them do, and it’s possible a social network based entirely on privacy can be successful, but 1) it would be challenging and 2) it's not clear many people mind trading off some privacy for showing off their best lives online.

This is, of course, exactly why many people love and choose Apple, and they have more cash than they can spend. No one need feel sorry for Apple, and as is often the case, a company’s strengths and weaknesses stem from the same quality in their nature. I’d rather Apple continue to focus on building the best computers in the world. Still, it’s a false tradeoff to regard Apple’s emphasis on privacy as an excuse for awkward interactions like photo sharing on iOS.

The same inherent social myopia applies to Google which famously took a crack at building a social network of its own with Google+. Like Apple, the team in Mountain View has always seemed more suited to building out networks of utility rather than social capital. Google is often spoken of as a company where software engineers have the most power. Engineers, in my experience, are driven by logic, and status-centered products are distasteful or mysterious to them, often both. Google will probably always be weak at social, but as with Apple, they compensate with unique strengths.

Oddly enough, despite controlling one of the two dominant mobile platforms, they have yet to be able to launch a successful messaging app. That’s about as utility-driven a social application as there is, akin to email where Google does have sizeable market share with GMail. It's a shame as Google could probably use social as an added layer of utility in many of their products, especially in Google Maps.

Amazon and Netflix both launched social efforts though they’ve largely been forgotten. It's likely the attempts were premature, pushed out into the world before either company had sufficient scale to enable positive flywheel effects. It’s hard enough launching a new social network, but it’s even harder to launch social features built around behaviors like shopping or renting DVD’s through the mail which occur infrequently. Neither company’s social efforts were the most elegantly designed, either (Facebook is underrated for its ability to launch a social product that scaled to billions of users, its design team has a mastery of maintaining ease of use for users of all cultures and ages).

Given the industrialization of fake reviews, and given how many people have Prime accounts, Amazon could build a social service simply to facilitate product recommendations and reviews from people you know and trust; I increasingly turn a skeptical eye to both extremely positive and negative reviews on Amazon, even if they are listed as coming from verified purchasers. The key value of a feature like this would be utility, but the status boost from being a product expert would be the energy turning the flywheel. The thing is, Amazon actually has a track record of harnessing social dynamics in service of its retail business with features like reviewer rankings and global sales rank (both are discussed a bit further down).

As for Netflix, I actually think social isn’t as useful as many would think in generating video recommendations (that’s a discussion for another day, but suffice it to say there is some narcissism of small differences when it comes to film taste). However, as an amplifier of Netflix as the modern water cooler, as a way to encourage herd behavior, social activity can serve as an added layer of buzz that for now is largely opaque to users inside Netflix apps. It's a strategy that is only viable if you can achieve the size of subscriber base that a Netflix has, and thus it is a form of secondary scale advantage that they could leverage more.

However, there's another reason that senior execs at most companies, even social networks, are ill-suited to designing and leveraging social features. It’s a variant of winner's curse.

Let Them Eat Cake

You'll hear it again and again, the easiest way to empathize with your users is to be the canonical user yourself. I tend to subscribe to this idea, which is unfortunate because it means I have hundreds of apps installed on my phone at any point in time, just trying to keep up with the product zeitgeist.

With social networks, one of the problems with seeing your own service through your users’ eyes is that every person has a different experience given who they follow and what the service's algorithm feeds them. When you have hundreds of millions or even billions of users, across different cultures, how do you accurately monitor what's going on? Your metrics may tell you that engagement is high and growing, but what is the composition of that activity, and who is exposed to what parts?

Until we have metrics that distinguish between healthy and unhealthy activity, social network execs largely have to steer by anecdote, by licking a finger and sticking it in the air to ascertain the direction of the wind. Some may find it hard to believe when execs plead ignorance when alerted of the scope of problems on their services, but I don't. When it comes to running a community, the thickest veil of ignorance is the tidy metrics dashboard that munges hundreds, thousands, or maybe even millions of cohorts into just a handful.

To really get the sense of a health of a social network, one must understand the topology of the network, and the volume and nature of connections and interactions among hundreds of millions or even billions of users. It’s impossible to process them all, but just as difficult today to summarize them without losing all sorts of critical detail.

But perhaps even more confounding is that executives at successful social networks are some of the highest status people in the world. Forget first world problems, they have .1% or .001% problems. On a day-to-day basis, they hardly face a single issue that their core users grapple with constantly. Engagement goals may drive them towards building services that are optimized as social capital games, but they themselves are hardly in need of more status, except of a type they won't find on their own networks.

[The one exception may be Jack Dorsey, as any tweet he posts now attracts an endless stream of angry replies. It’s hard to argue he doesn’t understand firsthand the downside risk of a public messaging protocol. Maybe, for victims of harassment on Twitter, we need a Jack that is less thick-skinned and stoic, not more.]

The Social Capital - Financial Capital Exchange

[If you fully believe in the existence and value of social capital, you can skip this section, though it may be of interest in understanding some ways to estimate its value.]

That some of the largest, most valuable companies in history have been built so quickly in part on creating status games should be enough to convince you of the existence and value of social capital. Since we live in the age of social media, we live in perhaps the peak of social capital assets in the history of civilization. However, as noted earlier, one of the challenges of studying it is that we don't have agreed-upon definitions of how to measure it and thus to track its flows.

I haven't found a clean definition of social capital but think of it as capital that derives from networks of people. If you want to explore the concept further, this page has a long list of definitions from literature. The fact is, I have deep faith in all my readers when it comes to social capital that, like Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart once said about pornography, you "know it when you see it."

But more than that, the dark matter that is social capital can be detected through those exchanges in which it converts into more familiar stores of value.

If you've ever borrowed a cup of milk from your neighbor, or relied on them to watch your children for an afternoon, you know the value of social capital. If you lived in an early stage of human history, when people wandered in small nomadic tribes and regularly clubbed people of other tribes to death with sticks and stones, you also know the value of social capital through the protective cocoon of its presence and the sudden violence in its absence.

Perhaps the easiest way to spot social capital is to look at places where people trade it for financial capital. With the maturing of social networks, we've seen the infrastructure to facilitate these exchanges come a long way. These trades allow us to assign a tangible value to social capital the way one might understand the value of an intangible assets like leveled-up World of Warcraft characters when they are sold on the open market.

Perhaps the most oft-cited example of a social-to-financial-capital exchange is the type pulled off by influencers on Instagram and YouTube. I've met models who, in another life, might be mugging outside an Abercrombie and Fitch or working the front door at some high end restaurant in Los Angeles, but instead now pull down over 7 figures a year for posting photos of themselves luxuriating in specific resorts, wearing and using products from specific sponsors. When Jake or Logan Paul post a video of themselves preening in front of their new Lamborghini in the driveway of the mansion they bought using money stemming from their YouTube streaming, we know some exchange of social capital for financial capital has occurred upstream. Reshape distribution and you reshape the world.

Similarly, we see flows the other direction. People buying hundreds of thousands of followers on Twitter is one of the cleanest examples of trading financial capital for social capital. Later, that social capital can be converted back into financial capital any number of ways, including charging sponsors for posts. Depending on the relative value in both directions there can be arbitrage.

[Klout, a much-mocked company online, attempted to more precisely track social capital valuations of people online, but, just as the truly wealthy mock the nouveau riche as gauche, many found the explicit measurement attempts unseemly. Most of these same people, however, compete hard for social capital online, so ¯\(ツ)/¯. The designation of which status games are acceptable is itself a status game.]

Asia, where monetization models differ for a variety of cultural and contextual reasons, provides an even cleaner valuation of social capital. There, many social networks allow you to directly turn your social capital into financial capital, without leaving the network. For example, on live-streaming sites like YY, you can earn digital gifts from your viewers which cost actual money, the value of which you split with the platform. In the early days, a lot of YY consisted of cute girls singing pop songs. These days, as seen in the fascinating documentary People’s Republic of Desire, it has evolved into much more.

Agencies have sprung up in China to develop and manage influencers, almost like farm systems in baseball with player development and coaches. The speed at which social capital can be converted into your own branded product lines is accelerating by leaps and bounds, and nowhere more so than in China.

Meanwhile, on Twitter, if one of your tweets somehow goes massively viral, you still have to attach a follow-up tweet with a link to your GoFundMe page, a vulgar monetization hack in comparison. It’s China, not the U.S., that is the bleeding edge of influencer industrialization.

I'm skeptical that all of Asia's monetization schemes will export to the culture in America, but for this post, the important thing is that social capital has real financial value, and networks differ along the spectrum of how easily that exchange can be made.

Social Capital Accumulation and Storage

As with cryptocurrency, it's no use accumulating social capital if you can't take ownership of it and store it safely. Almost all successful social networks are adept at providing both accumulation and storage mechanisms.

It may sound obvious now, but consider the many apps and services that failed to provide something like this and saw all their value leak to other social networks. Hipstamatic came before Instagram and was the first photo filter app of note that I used on mobile. But, unlike Instagram, it charged for its filters and had no profile pages, social network, or feed. I used Hipstamatic filters to modify my iPhone photos and then posted them to other social networks like Facebook. Hipstamatic provided utility but captured none of the social capital that came from the use of its filters.

Contrast this with a company like Musical.ly, which I mentioned above. They came up with a unique proof of work burden, but unlike Hipstamatic, they wanted to capture the value of the social capital that its users would mine by creating their musical skits. They didn't want these skits to just be uploaded to Instagram or Facebook or other networks.

Therefore, they created a feed within the app, to give its best users distribution for their work. By doing so, Musical.ly owned that social capital it helped generate. If your service is free, the best alternative to capturing the value you create is to own the marketplace where that value is realized and exchanged.

Musical.ly founder Alex Zhu likens starting a new social network to founding a new country and trying to attract citizens from established countries. It's a fun analogy, though I prefer the cryptocurrency metaphor because most users are citizens of multiple social networks in the tech world, managing their social capital assets across all of those networks as a sort of diversified portfolio of status.

For the individual user, we've standardized on a few basic social capital accumulation mechanisms. There is the profile, to which your metrics attach, most notably your follower count and list. Followers or friends are the atomic unit of many social networks, and the advantage of followers as a measure is it generally tends to only grow over time. It also makes for an easy global ranking metric.

Local scoring of social capital at the atomic level usually exists in the form of likes of some sort, one of the universal primitives of just about every social network. These are more ephemeral in nature given the nature of feeds, which tend to prioritize distribution of more recent activity, but most social networks have some version of this since followers tend to accumulate more slowly. Likes correlate more strongly with your activity volume and serve as a source of continual short-term social capital injections, even if each like is, in the long-run, less valuable than a follower or a friend.

Some networks allow for accelerated distribution of posts through resharing, like retweeting (with many unintended consequences, but that's a discussion for another day). Some also allow comments, and there are other network-specific variants, but most of these are some form of social capital that can attach to posts.

Again, this isn't earth-shattering to most users of social networks. However, where it’s instructive is in examining those social networks which make such social capital accumulation difficult.

A good example is the anonymous social network, like Whisper or Secret. The premise of such social networks was that anonymity would enable users to share information and opinions they would otherwise be hesitant to be associated with. But, as is often the case, that strength turned out to be a weakness, because users couldn't really claim any of the social capital they'd created there. Many of the things written on these networks were so toxic that to claim ownership of them would be social capital negative in the aggregate.

A network like Reddit solved this through its implementation of karma, but it's fair to say that it's also been a long struggle for Reddit to suppress the dark asymmetric incentives unlocked by detaching social capital from real-life identity and reputation.

[Balaji Srinivasan once mentioned that someday the cryptocurrencies might allow someone to extract the value from an anonymous social network without revealing their identity publicly, but for now, at least, a lot of this status on social networks isn’t monetary in nature. A lot of it’s just for the lulz.]

For any single user, the stickiness of a social network often correlates strongly with the volume of social capital they've amassed on that network. People sometimes will wholesale abandon social networks, but it's rare unless the status earned there has undergone severe deflation.

Social capital does tend to be non-fungible which also tends to make it easier to abandon ship. If your Twitter followers aren't worth anything on another network, it's less painful to just walk away from the account if it isn't worth the trouble anymore. It's strange to think that social networks like Twitter and Facebook once allowed users to just wholesale export their graphs to other networks since it allowed competing networks to jumpstart their social capital assets in a massive way, but that only goes to show how even some of the largest social networks at the time underestimated the massive value of their social capital assets. Facebook also, at one point, seemed to overestimate the value of inbound social capital that they'd capture by allowing third party services and apps to build on top of their graph.

The restrictions on porting graphs is a positive from the perspective of the incumbent social networks, but from a user point-of-view, it's frustrating. Given the difficulty of grappling with social networks given the consumer welfare standard for antitrust, an option for curbing the power of massive network effects businesses is to require that users be allowed to take their graph with them to other networks (as many have suggested). This would blunt the power of social networks along the social capital axis and force them to compete more on utility and entertainment axes.

Social Capital Arbitrage

Because social networks often attract different audiences, and because the configuration of graphs even when there are overlapping users often differ, opportunities exist to arbitrage social capital across apps.

A prominent user of this tactic was @thefatjewish, the popular Instagram account (his real name was Josh Ostrovsky). He accumulated millions of followers on Instagram in large part by taking other people's jokes from Twitter and other social networks and then posting them as his own on Instagram. Not only did he rack up followers and likes by the millions, he even got signed with CAA!

When he got called on it, he claimed it wasn't what he was about. He said, "Again, Instagram is just part of a larger thing I do. I have an army of interns working out of the back of a nail salon in Queens. We have so much stuff going on: I'm writing a book, I've got rosé. I need them to bathe me. I've got so many other things that I need them to do. It just didn't seem like something that was extremely dire." Which is really a long, bizarre way of saying, you caught me. Let he who does not have an army of interns bathing them throw the first stone.

Since then, similar joke aggregator accounts on Instagram have continued to proliferate, but some of them now follow the post-fatjewish-scandal social norm of including the proper attribution for each joke in the photo (for example including the Twitter username and profile pic within the photo of the “borrowed” tweet). But many do not, and even for those who do, the most prominent can trigger a backlash. The hashtag #fuckfuckjerry is an emergent protest against the popular Instagram account @fuckjerry which, like @fatjewish, curates the best jokes from others and daytraded that into a small media company, one that featured in the Fyre Festival debacle.

As long as we have multiple social networks that don't quite work the same way, there will continue to be these social media arbitragers copying work from one network and to a different network to accumulate social capital on closing the distribution gap. Before the internet, men resorted to quoting movies or Mitch Hedberg jokes in conversation, to steal a bit of personality and wit from a more gifted comedian. This is the modern form of that, supercharged with internet-scale reach.

At some level, a huge swath of social media posts are just attempts to build status off of someone else's work. The two tenets at the start of this article predict that this type of arbitrage will always be with us. Consider someone linking to an article from Twitter or Facebook, or posting a screenshot of a paragraph from someone else's book. The valence of the reaction from the original creators seems to vary according to how the spoils of resharing are divvied up. The backlash to Instagram accounts like @thefatjewish and @fuckjerry may stem from the fact that they don't really share value from those whose jokes they redistribute, whereas posting an excerpt from a book on Twitter, for example, generates welcome publicity for the author.

Social Capital Games as Temporary Energy Sources

Structured properly, social capital incentive structures can serve as an invaluable incentive. For example, curation of good content across the internet remains an never-ending problem in this age of infinite content, so offering rewards for surfacing interesting things remains one of the oldest and most reliable marketplaces of the internet.

A canonical example is Reddit, where users bring interesting links, among other content, in exchange for a currency literally named karma. Accumulate enough karma and you'll unlock other benefits, like the ability to create your own subreddit, or to join certain private subreddits.

Twitter is another social network where people tend to bring interesting content in the hopes of amassing more followers and likes. If you follow enough of the right accounts, Twitter becomes an interestingness pellet dispenser.

Some companies which aren't typically thought of as social networks still turn to social capital games to solve a particular problem. On one Christmas vacation, I stumbled downstairs for a midnight snack and found my friend, a father of three, still up, typing on his laptop. What, I asked, was he doing still up when he had to get up in a few hours to take care of his kids? He was, he admitted sheepishly, banging out a litany of reviews to try to maintain his Yelp Elite status. To this day, some of my friends still speak wistfully about some of the Yelp Elite parties they attended back in the day.

Think of how many reviews Yelp accumulate in the early days just by throwing a few parties? It was, no doubt, well worth it, and at the point when it isn't (what's the marginal value of writing the, at last count, 9655th review of Ippudo in New York City?), it's something easily dialed back or deprecated.

Amazon isn't typically thought of as a company that understands social, but in its earliest days, before even Yelp, it employed a similar tactic to boost its volume of user reviews. Amazon Top Reviewers was a globally ranked list of every reviewer on all of Amazon. You could boost your standing by accumulating more useful review votes from shoppers for your reviews. I'll always remember Harriet Klausner, who dominated that list for years, reviewing seemingly every book in print. Amazon still maintains a top customer reviewer list, but it has been devalued over time as volume of reviews is no longer a real problem for Amazon.

Another example of a status game that Amazon employed to great effect, and which doesn't exist anymore, was Global Sales Rank. For a period, every product on Amazon got ranked against every other product in a dynamic sales rank leaderboard, and the figure would be displayed prominently near the top of each product detail page. Book authors pointed customers to Amazon to buy their books in the hope of goosing their sales rank the same way authors today often commit to buy some volume of their own book when it releases in the hopes of landing on the NYTimes bestseller list the week it releases.

IMDb and Wikipedia are two companies which built up entire valuable databases almost entirely by building mechanisms to harness the equal mix of status-seeking and altruism of domain experts. As with Reddit, accumulating a certain amount of reputation on these services unlocked additional abilities, and both companies built massive databases of information with very low production and editorial costs.

You can think of social capital accumulation incentives like these as ways to transform the potential energy of status into whatever form of kinetic energy your venture needs.

Why Most Celebrity Apps Fail

For a while, a trend among celebrities was to launch their own app. The Kardashian app is perhaps the most prominent example, but there are others.

From a social capital perspective, these create little value because they simply draw down upon the celebrity's own status. Almost every person who joins just wants content from the eponymous celebrity. The volume of interaction between the users of the app themselves, the fans, is minimal to non-existent. Essentially these apps are self-owned distribution channels for the stars, and as such, they tend to be vanity projects rather than durable assets.

One can imagine such apps trying to foster more interaction among the users, but that is a really complex effort, and most such efforts have neither the skills to take this on nor the will or capital necessary to see it through.

Another way to think of all these celebrity ventures is to measure the social capital and utility of the product or service if you remove all the social capital from the celebrity in question. A lot minus a lot equals zero.

Conclusion: Everybody Wants to Rule the World

In the immortal words of Obi-Wan Kenobi, "Status is what gives a Jedi his power. It's an energy field created by all living things. It surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the galaxy together."

That many of the largest tech companies are, in part, status as a service businesses, is not often discussed. Most people don't like to admit to being motivated by status, and few CEO's are going to admit that the job to be done for their company is stroking people’s egos.

From a user perspective, people are starting to talk more and more about the soul-withering effects of playing an always-on status game through the social apps on their always connected phones. You could easily replace Status as a Service with FOMO as a Service. It’s one reason you can still meet so many outrageously wealthy people in Manhattan or Silicon Valley who are still miserable.

This piece is not my contribution to the well-trod genre of Medium thinkpieces counseling stoicism and Buddhism or transcendental meditation or deleting apps off of your phone to find inner peace. There is wisdom in all of those, but if I have anything to offer on that front, it’s this: if you want control of your own happiness, don’t tie it to someone else’s scoreboard.

Recall the wisdom of Neil McCauley in the great film Heat.