And You Will Know Us by the Company We Keep

It feels as if we're at the tail end of the first era of social media in the West. Looking back at the companies that have survived, certain application architectural choices are ubiquitous. By now, we're all familiar with the infinite vertical scrolling feed of content units, the likes, the follows, the comments, the profile photos and usernames, all those signature design tropes of this Palaeozoic era of social.

But just as there are reasons why these design patterns won out, we shouldn't let survivor bias blind us to their inherent tradeoffs. The next wave of social startups should learn from the weaknesses of some of these choices of our current social incumbentsIt's easy to point out where our incumbent social networks went wrong. Of course, to be where they are today, they had to do a hell of a lot right, too. A lot of mistakes are understandable in hindsight given that online networks of this scale hadn't been built in history before. Still, it's easier to learn from where they went wrong if we're to head towards greener pastures.. It's never smart to tackle powerful incumbents head on anyway. The converged surface area in the design of all these apps suggest oblique vectors of attack.

While many of these flaws have already been pointed out and discussed in various places, one critical design mistake keeps rearing its head in many of the social media Testflights sent my way. I've mentioned it in various passing conversations online before. I refer to this as the problem of graph design:

When designing an app that shapes its user experience off of a social graph, how do you ensure the user ends up with the optimal graph to get the most value out of your product/service?

The fundamental attribution error has always been one of my cautionary mental models. The social media version of this is over-attributing how people behave on a social app to their innate nature and under-attributing it to the social context the app places them in. Perhaps the single most important contextual influence in social media is one's social graph. Who they follow and who follows them.

Just as some sharks that stop moving dieSome sharks rely on ram ventilation must swim in order to push water over their gills to breathe. But many shark species do not. Maybe we should refer to social apps that rely on a graph to work as "graph ventilated.", most Western social media apps must build a graph or die. This is because most of the most well-known Western social apps chose to interlace two things: the social graph and the content feed. That is, the most social media apps serve up an infinite vertical scrolling feed populated by content posted by the accounts the user follows. In my essay series on TikTok (in order, they are TikTok and the Sorting Hat, Seeing Like an Algorithm, and American Idle), I refer to this as approximating an interest graph using a social graph.

You can see this time-tested design, for example, in Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. It is particularly suited to mobile phones, which dominate internet usage today, and which offer a vertical viewport when held in portrait orientation, as they most often are.

We'll return, in a second, to whether this choice makes sense. For now, just note that this architecture behooves these apps to prioritize scaling of the social graph. It's imperative to get users to follow people from the jump. Otherwise, by definition, their feeds will be empty.

This is the classic social media chicken-and-egg cold start problem. Every Silicon Valley PM has likely heard the stories about how Twitter and Facebook's critical keystone metrics were similar: get a user to follow some minimum number of accounts. Achieve that and those users turn into WAUs, or even better, DAUs. Users failing to follow enough accounts were the most likely to churn. Many legendary growth teams built their entire reputations inducing tens or hundreds of millions users to follow as many other users as possible.

But, again, this obligation derives entirely from the choice to build the feed directly off of the social graph. In TikTok and the Sorting Hat, I wrote:

But what if there was a way to build an interest graph for you without you having to follow anyone? What if you could skip the long and painstaking intermediate step of assembling a social graph and just jump directly to the interest graph? And what if that could be done really quickly and cheaply at scale, across millions of users? And what if the algorithm that pulled this off could also adjust to your evolving tastes in near real-time, without you having to actively tune it?

The problem with approximating an interest graph with a social graph is that social graphs have negative network effects that kick in at scale. Take a social network like Twitter: the one-way follow graph structure is well-suited to interest graph construction, but the problem is that you’re rarely interested in everything from any single person you follow. You may enjoy Gruber’s thoughts on Apple but not his Yankees tweets. Or my tweets on tech but not on film. And so on. You can try to use Twitter Lists, or mute or block certain people or topics, but it’s all a big hassle that few have the energy or will to tackle.

Almost all feeds end up vying with each other in the zero sum attention landscape, and as such, they all end up getting pulled into competing on the same axis of interest or entertainment. Head of Instagram Adam Mosseri recently announced a series of priorities for the app in the coming year, one of them being an increased focus on video. “People are looking to Instagram to be entertained, there’s stiff competition and there’s more to do,” Mosseri said. “We have to embrace that, and that means change.”

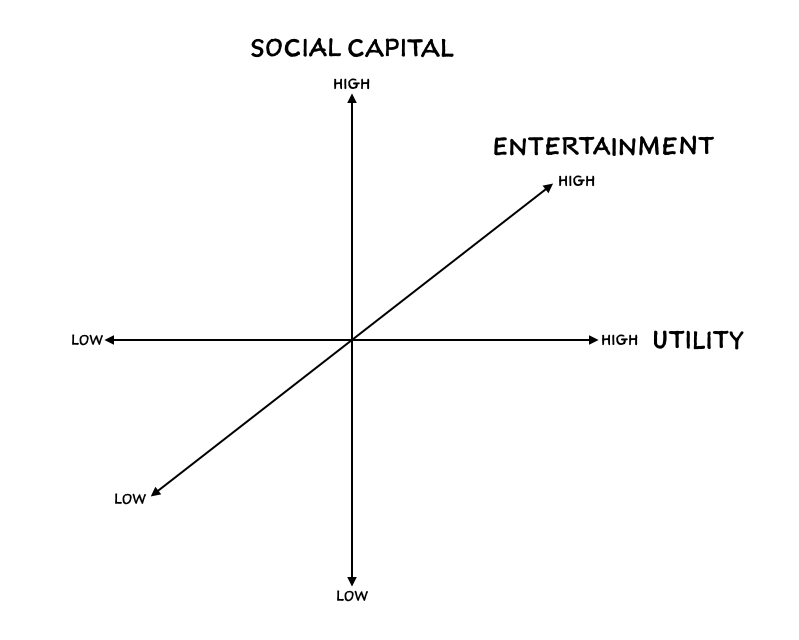

In my post Status as a Service, I noted that social networks tend to compete on three axes: social capital, entertainment, and utility. Focusing just on entertainment, the problem with building a content feed off of a person's social graph is that, to be blunt, we don't always find the people we know to be that entertaining. I love my friends and family. That doesn't mean I want to see them dancing the nae nae. Or vice versaEDITOR'S NOTE: It's not just people who know him. No one wants to see Eugene dance the nae nae.. Who we follow has a disproportionate effect on the relevance and quality of what we see on much of Western social media because the apps were designed that way.

At the same time, who follows us may be just as consequential. We tend to neglect that in our discussions of social experiences, perhaps because it's a decision over which users have even less control than who they choose to follow. Yet it shouldn't come as a surprise that what we are willing to post on social media depends a lot on who we believe might see it. Our followers are our implied audience.

To take the most famous example, the root of Facebook's churn issues began when their graph burgeoned to encompass everyone in one's life. As noted above, just because we are friends with someone doesn't mean we want to see everything they post about in our News Feed. In the other direction, having many more people from all spheres of our lives follow us created a massive context collapse. It wasn't just that everyone and their mother had joined Facebook, it was specifically that everyone's mother had joined Facebook.There's some generalizable form of Groucho's Marx quip about not refusing to join any club that would have him as a member. Namely, that most people don't want to belong to a club where they're the highest status member. Because, by definition, the median status of a member of the club is lowering their own. That's not to say it can't be a stable configuration. Networks based more around utility, like WeChat, aren't driven as much by status dynamics. Not surprisingly, they are less focused on a singular feed.

It's difficult, when you're starting out on a social network, to imagine that having more followers could be a bad thing. Yet many Twitter users complain after they surpass 20K, then 50K, then 100K followers or more. Suddenly, a lot of your hot takes attract equally hot pushback. Suddenly, it isn't so fun yeeting your ideas out into the ether. I know. Boo hoo on the smallest violin. But regardless of whether you think this is a first world problem, it's indicative of how phase shifts in the experience of social media are difficult to detect until long after they've occurred.

To put it even stronger, graph design problems are particularly dangerous to social companies because they fall into that class of mistakes that are difficult to reverse. Jeff Bezos wrote, in his 1997 Amazon letters to shareholders, about two types of decisions.

Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible – one-way doors – and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions. But most decisions aren’t like that – they are changeable, reversible – they’re two-way doors. If you’ve made a suboptimal Type 2 decision, you don’t have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

Graph design problems are one-way mistakes in large part because users make them so. Most social media users don't unfollow people after following them. Much of this comes down to social conformity. It's awkward and uncomfortable to do so, especially if you'll run into them. Anytime I unfollow someone I might run into, I imagine them cornering me like Larry David at the water cooler, eyebrows raised, with that signature tone of voice he mastered on Curb Your Enthusiasm, an equal mix of indignation at being slighted and glee at having caught you in an act of hypocrisy. "So, Eugene, I notice you unfollowed me. Pret-tay, pret-tay interesting."

If people tend to add to their social graphs more than they prune them, the social graph you help your users design should be treated as a one-way decision. And as Bezos noted, one-way decisions should be treated with care.Once Twitter started posting tweets to my timeline simply because people I followed had liked them, even if they were tweets from people I didn't follow myself, I started getting very confused. If you're angry I don't follow you, it may be that I think I already follow you.

Many social apps, because of how they're configured, undergo phase shifts as the graph scales. The user experience at the start, when you have few friends and followers, changes as those figures rise. At first, it's more lively with more people. Now the party's getting started. But beyond some scale, negative network effects creep in. And if you don't change how you handle it, before you know it, you find yourself pronouncing that you're taking a break from social media for your mental health.

Not only do users not notice it happening, like the proverbial slow boiling frog, the people operating the apps may be oblivious to the phase shifts until it's too late. Social graphs are path dependent.

A classic example, though I don't know if this still persists, is how Pinterest skewed heavily towards female users at launch, losing lots of potential male users in the process. This was a function of building their feed off of each user's social graph. Men would see a flood of pins from the females in their network as women were some of the strongest earlier adopters of pinning. This created a reflexive loop in which Pinterest was perceived as a female-centric social app, which chased off some male users, thus becoming self-fulfilling stereotype. An alternate content selection heuristic for the feed could have corrected for this skew.

But again, this is a problem unique to Western social media design. In conflating the social graph and the interest graph, we've introduced a content matching problem that needn't exist. I don't get upset that my friends don't follow me on TikTok or Reddit or what I think of as purer interest and/or entertainment networks. It's very clear in those products that each person should follow their own interests.

The way China has built out its social infrastructure is, in at least this respect, more logical. WeChat owns the dominant social graph, and it acts as an underlying social infrastructure to the rest of the Chinese internetThough not always a reliable one. If you're a WeChat competitor in any category, they may block links to your apps, as they've done with Douyin and Taobao in the past. This is always the danger of a private company owning the dominant social graph, and where regulators need to step in.. Rather than duplicate the social graph of everyone, which WeChat owns, other apps can focus on what they do best, which might or might not require an alternate graph.

Western social apps also rely much more heavily on advertising revenue. The lifeblood of their income statement is traffic to the feed. This means feed relevance is paramount. Anywhere one's social graph drifts from one's interests, boring content invades the feed. The signal to noise ratio shifts the wrong direction. Instead of pruning and tuning their social graphs to fix their feeds, most users do the next easiest thing: they churn.

As a product manager or designer on social app, you might object. The user chooses who to follow, and other users choose to follow them. It's out of your control. But this ignores all the ways in which apps put their hands on the scale to nudge each user towards a specific type of graph.

Take initial user sign-up flows. Every week, I seem to encounter this modal dialog on a new social app Testflight:

What I look for is where this request appears and how the app frames it. Most times, users are asked to grant access to their contact book and to follow any matching users (or even worse, to spam their contact list with invites) before they have any idea of what the app is even about. In pushing people to duplicate their contact book, these apps are explicitly choosing to build off of people's real-world social graphs.

It's not surprising that social apps prioritize this permission as a critical one in the sign-up flow. The iOS contact book is now the only "open-source" social graph that a new app can work from to jumpstart their own. In The Network's the Thing, I argued that the network itself provides the lion's share of the value for a social network, that arguments about what types of content to allow in feeds, how those were formatted, were of much less importance. For a brief window, massive social graphs like Facebook or Twitter allowed third-party apps to tap into those graphs, even to duplicate them wholesale.

Instagram famously got a nice head start on building out their own social graph by siphoning off of Twitter's. It didn't take long for those companies to realize that they were arming their future competition. They clamped down on graph access hard. You can still offer Facebook or Twitter auth as an option for your app, but if you want a social graph of your own, the mobile contact book is the easiest to tap into nowadays.

Another way apps really influence the shape of their social graph is with suggested follow lists. These often appear in the first-time user walkthrough, interspersed in the feed, and sometimes alongside the feed.

Early Twitter users fortunate enough to be on the first versions of Twitter's suggested follow list today have hundreds of thousands or even millions of followers because they were paraded in front of every new user.

It was a massive social capital subsidy, but I find a lot of selections on that list puzzling. A few years ago, a friend set up a Twitter account for the first time and showed me the list of accounts Twitter suggested to them during sign up. It included Donald Trump. Which, regardless of your political leanings, is a dubious choice. Let's just shove every new user in the direction of politics Twitter (I'd be skeptical of a suggestion of Biden, too), one of the worst Twitters there is. Cool, cool.

For some people, like those who frequent fight clubs on weekends, politics Twitter might be the perfect dopamine fix, but when a user is signing up for the first time and Twitter knows nothing about them, that's a bizarre gamble to take.

For years, people marveled at Facebook's Suggested Friends widget. Wow, how did they know that I knew that person, yes, of course I'll friend them. And yet, as noted earlier, that may have been a graph design mistake given the way the News Feed was being constructed.

In the other direction, it's also important to help a users acquire the right types of followers. Cults are held together by a bi-directional influence. Cult leaders use their charisma to grow a following, then those followers shape the cult leader in return. It's a symbiotic feedback loop, not always a healthy one.

Besides being one-way mistakes, graph design errors are also pernicious because the tend to manifest only after an app has achieved some level of product-market fit. By that point, not only is it difficult to undo the social graph that has crystallized, to do so would violate the expectations of the users who've embraced the app as it is. It's a double bind, you're damned if you do and damned if you don't. Apps that achieve some level of product-market fit, even if it's a local maximum, require real courage to revert.

This doesn't stop social apps from trying to fix the problem. Reduced traffic to the feed is existential for many social apps. Instead of fixing the root problem of the graph design, however, most apps opt instead to patch the problem. The most popular method is to switch to an algorithmic, rather than chronological, feed. The algorithm is tasked with filtering the content from the accounts you've chosen to follow. It tries to restore signal over noise. To determine what to keep and what to toss, feed algorithms look at a variety of signals, but at a basic level they are all trying to guess what will engage you.

Still, this is a band-aid on an upstream error. Look at Facebook oscillating every few years between news content and more personal content from people you know. Until they acknowledge that the root problem lies in sourcing stories for News Feed from their monolithic social graph, they'll never truly solve their churn. And yet, to walk away from this fundamental architecture of their News Feed would be the boldest decision they've made in their long historyIronically, shifting to the News Feed itself was perhaps their previous boldest decision.. Not just because almost all their revenue comes from News Feed as it works now, but also since assembling a monolithic graph might be their strongest architectural defense against government antitrust action.

Twitter, unlike Facebook with its predominant two-way friending, is built on a graph assembled from one-way follows. In theory, this should reduce its exposure to graph design problems. However, it suffers from the same flaw that any interest graph has when built on a social graph. You may be interested in some of a person's interests but not their others. Twitter favors pure play Twitter accounts that focus on one niche. But most people don't opt to operate multiple Twitter accounts to cleanly separate the topics they like to tweet about.

One of my favorite heuristics for spotting flaws in a system is to look at those trying to break it. Advanced social media users have long tried to hack their away around graph design problems. Users who create finsta's or alt Twitter accounts are doing so, in part, to create alternative graphs more suited to particular purposes. One can imagine alternative social architectures that wouldn't require users to create multiple accounts to implement these tactics. But in this world where each social media account can only be associated with one identity, users are locked into a single graph per account.

One clever way an app might help solve the graph design problem is by removing the burden of unfollowing accounts that no longer interest users. Just as our social graphs change throughout our lives, so could our online social graphs. Our set of friends in kindergarten tend not to be the same friends we have in grade school, high school, college, and beyond.

A higher fidelity social product would automatically nip and tuck our social graphs over time as they observed our interaction patterns. Imagine Twitter or Instagram just silently unfollowing accounts you haven't engaged with in a while, accounts that have gone dormant, and so on. Twitter and Facebook offer methods like muting to reduce what we see from people without unfriending or unfollowing, but it's a lot of work, and frankly I feel like a coward using any of those.

Messaging apps, by virtue of focusing on direct communication between two people or among groups, naturally achieve this by pushing the threads with the latest messages to the top of their application windows. People who fall out of our lives just fall off the bottom of the screen. LIFO has always been a reasonably effective general purpose relevance heuristic.

Another possible solution to the graph design problem is to decouple a users content feed from their social graph. In my three pieces on TikTok, I wrote about how that app's architecture is fundamentally different from that of most Western social media. TikTok doesn't need you to follow any accounts to construct a relevant feed for you. Instead, it does two things.

First, it tries to understand what interests you by observing how you react to everything it shows you. It tries to learn your taste, and it does a damn good job of it. TikTok is an interest graph built as an interest graph.

Secondly, TikTok runs every candidate video through a two-stage screening process. First, it runs videos through one of the most terrifying, vicious quality filters known to man: a panel of a few hundred largely Gen Z users.Okay, yes, that's not quite right. Anyone can be on this test audience for a video. It just happens, however, that TikTok's user base skews younger, so most of the people on that panel will be Gen Z. Also, it's a known fact that a pack of Gen Z users muttering "OK Boomer" is the most terrifying pack hunter in the animal kingdom after hyenas and murder hornets. If those test viewers don't show any interest, the video is yeeted into the dustbin of TikTok, never to be seen again except if someone seeks it out directly on someone's profile.

Secondly, it then uses its algorithm to decide whether that video would interest each user based on their taste profile. Even if you don't follow the creator of a video, if TikTok's algorithm thinks you'll enjoy it, you'll see it in your For You Page.

Recently, Instagram announced it would start showing its users posts from accounts they don't follow. In many ways, this is as close to a concession as we'll see from Instagram to the superiority of TikTok's architecture for pure entertainment.

Some apps use some sort of topic or content picker. Tell us what music or film genres you like. What news topics interest you. Then they try to use machine learning and signals from their entire user base to serve you a relevant feed.

The effectiveness of this approach varies widely. Why does a playlist generated off a single song on Spotify work so well and yet its podcast recommendations feel generic? Why, after spending years and millions of dollars on research, including the fabled Netflix prize, do Netflix's recommendations still feel generic, and why doesn't it really matter? Why are book recommendations on Amazon solid while article recommendations on news sites feel random? It would take an entire separate piece just to dig into why some content recommendations work so much better than others, so complex is the topic.

In this piece focused on graph design, what matters is that things like content pickers explicitly veer away from the social graph. Twitter allowing you to follow topics in addition to accounts can be seen as one attempt to move a half step towards being a pure interest graph.

It's not that apps can't be more fun when social, or that people don't share some overlapping interests with people they know. We all care both our interests and the people in our lives. When they overlap, even better. It's just that after more than a decade of living with our current social apps, we have ample case studies illustrating the downsides of assuming they are perfectly correlated.

A secondary consideration is what type of interaction an application is building towards in the long run. Is is about one-to-one interactions or broadcasting to large audiences? What percentage of your users do you want creating as opposed to just consuming? Is your app best served by a graph of people who know each other in real life or by a graph that connects strangers who share common interests? Or some mix of both? Is your app for people from the same company or organization? Will the interactions cut across cultures and national borders, or is it best if various geographies are segregated into their own graphs?

The next generation of social product teams can and should be more proactive about thinking through what type of social graph will offer the best user experience in the long run.

I'm not certain, but it doesn't feel, based on the histories I've heard, that many social networks built their graphs with a particular design in mind. This makes graph design an exercise with more open questions than answers. In some ways, Facebook being built for just Harvard students in the beginning may have imposed some helpful graph design constraints by chance.

Unlike some types of design, graph design doesn't lend itself easily to prototyping. Social networks are at least in part complex adaptive systems, making it difficult to prototype what types of interactions will occur if and when the graph achieves scale.

But whereas traditional complex adaptive systems are so complex that predictions are futile, social networks are different in two ways. One is that human nature is consistent. The second is that we have numerous super scaled social networks to study. They're massive real world test cases for what happens when you make certain choices in graph design.

They also exist in multiple markets around the world. This makes it possible to study distinct path dependencies, especially when comparing across cultures and market conditions as unique as China versus the U.S. Despite all the variations in context, issues like trolling seem universal, suggesting that some potent underlying mechanisms are at work.

Once you tug on the threads surrounding graph design, you can burrow deep down many rabbit holes. If the people connected are going to be complete strangers, how will you establish sufficient trust (e.g. through a reputation system)? If the trunk of the app is a content feed, does that feed have to draw exclusively from stories posted by accounts followed by the user? Does it have to pluck candidates from those accounts at all? Is a feed even the right architecture for healthy interactions among your users?

Whose job is it to consider the problem of graph design? And when? To take one example, growth team strategies should be informed by your graph design. Growth shouldn't be treated as a rogue team whose only job is to extend the graph in every possible direction. They need to know what both good and harmful graph growth looks like so they can craft strategies more aligned with the long term vision.

Recently, TikTok started pushing me to connect more with people I know IRL. I've gotten prompts asking me to follow people I may know, and now when I share videos with people, I often get a notification telling me they've watched the video I've shared. Often these notifications are the only way I know they even have a TikTok account and what their username is.

To date, I've enjoyed TikTok without really following any people I know IRL. Perhaps TikTok is trying to make sharing of its videos endogenous to the app itself. But by this point in my piece, it should be obvious that I consider any changes to the graph of any social product to be moves that should be treated with greater caution. Most people I know don't make any TikToks (I know, I know, this is how you can tell I'm old), so following them won't impact my FYP much. For a younger cohort, where users make TikToks at a much higher rate, following each other may make more sense.

On the other hand, any app with a default public graph structure plays into the innate human impulse to judge. Wait, this person I know follows which accounts on TikTok?! Tsk tsk.

The answer to whether TikTok should push its users to replicate their real world social graphs isn't cut and dried. I bring it up only to illustrate that graph design is a discipline that requires deeper consideration. It could use, as its name implies, some design.

The term "follow" is fitting. Who we follow can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. First you build your graph, then your graph builds you. Plenty of research shows that humans tend to oscillate at the same frequency as the people they spend the most time with. Silicon Valley sage Naval Ravikant popularized the 5 Chimp Theory from zoology, which says you can deduce the mood and behavior of any single chimp by observing by which five chimps they hang out with the most.

The social media version of this is that we can predict how any user will behave on an app by the people they follow, the people who follow them, and the "space" they're forced to interact with those people in, be it a Facebook News Feed or Twitter Timeline or other architecture. We all know people who are the worst versions of themselves on social media. The fundamental attribution error predicts we'll think they're terrible by nature when they may just be responding to their environment and incentives.

Humans aren't chimps, we tend to juggle membership in dozens of different social groups at a time. Reed's Law predicts that the utility of networks scales exponentially because not only can each person in a network connect with every other node, but the number of possible subgroups is 2^N-N-1 where N is the number of people in that network.

But whether a social app allows such subgroups to form easily is a design problem. Monolithic feeds tend to force people into larger subgroups than is optimal for healthy interaction. While every user sees a different Twitter Timeline or Facebook News Feed, the illusion is still of a large public commons. Because anyone might see something you post, you should operate as if everyone will.

Messaging apps, in contrast, tend to allow users themselves to form the subgroups most relevant to them. Facebook Groups is a more flexible architecture than News Feed. Humans contain multitudes, and social apps should flex to their various communication privacy needs.

It's no surprise that many tech companies install Slack and then suddenly find themselves, shortly thereafter, dealing with employee uprisings. When you rewire the communications topology of any group, you alter the dynamic among the members. Slack's public channels act as public squares within companies, exposing more employees to each other's thoughts. This can lead to an employee finding others who share what they thought were minority opinions, like reservations about specific company policies. We're only now seeing how many companies operated in relative peace in the past in large part because of the privacy inherent in e-mail as a communications technology.

In many ways, graph design was always bound to be more important in Western social media now, in the year 2021, than in the early days of social media. In the early days of the internet, the public social graph was sparse to non-existent. For the most part, our graphs were limited to the email addresses we knew and the occasional username of someone in our favorite news groups. It's hard to explain to a generation that grew up with the internet what a secret thrill every new connection online was in the early days of the internet. How hard it was to track down someone online if all you knew was their name.

Today, we have more than enough ways to connect to just about anybody in the world. Adding someone to my address book feels almost unnecessary when I can likely reach any person with a smartphone and internet access any of a dozen ways.

In a world where finding someone online is a commodityOne sign that it is a commodity is that messaging apps, while massive, are for the most part lousy businesses that generate little in revenue. That's the financial profile you'd expect of a commodity business., the niftier trick is connecting to the right people in the right context. I have over a dozen messaging apps installed on my phone, they all look roughly the same. While I've discussed graph design largely defensively here—how to avoid mistakes in graph design—the positive view is to use graph design offensively. How do you craft a unique graph whose very structure encodes valuable, and more importantly, unique intelligence?

LinkedIn may be the social app Silicon Valley product people like to grouse about the most, but while many of the complaints are valid, its sizable market cap is testament to the value of its graph. It turns out if you map out the professional graph, not just today but also across long temporal and organizational dimensions, recruiters will pay a lot of money to traverse it.

For all the debate over whether our current social networks are good for society, I prefer to focus on the potential we've yet to realize. We have the miracle of Wikipedia, yes, but aren't there more types of mass scale collaboration to be enabled?

Every other week or so, I am introduced to someone amazing, or an account I've never heard of before that blows me away. That social networks themselves aren't facilitating these introductions leaves me less sad than hopeful. In a decade, today's social graphs will look like blunt instruments, so primitive were their configurations.

We'll also look back over that decade, see how many more amazing people we finally met at the right time and the right context, and realize that indeed, the real treasure was the friends we made along the way.