How to Blow Up a Timeline

NOTE: I’d been working on this piece on and off for a few weeks while trying to move to NYC and settle into my new apartment, and just as I was about to publish it, Elon rate-limited Twitter and so, sensing a moment of weakness, Meta pulled up its launch date for Threads to yesterday. This piece doesn’t cover Threads directly, nor does it talk about the rate-limiting fiasco. It’s focused on why I think Twitter got so much worse over the past year. I thought about holding off and reworking it entirely to incorporate all that happened this week, but in the end I decided that it was cleaner to publish this one as is. If Twitter hadn’t botched so much over this past year, Threads wouldn’t matter. Still, like past pieces I’ve written on topics related to Twitter, you can apply a lot of the ideas in this piece to analyzing Threads’ prospects. And I’ll push a follow-up piece with my specific reactions to and predictions for Threads soon-ish. Follow me on Substack to get a note when that drops.

“I shall be writing about how cities work in real life, because this is the only way to learn what principles of planning and what practices in rebuilding can promote social and economic vitality in cities, and what practices and principles will deaden these attributes.” — Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

Today, I come to bury Twitter, not to appraise him.

Oh, who am I kidding, I’m mostly here to appraise how it blew up.

For years, I thought Twitter would persist like a cockroach because:

- At its core, it’s a niche experience that alienates most but strongly appeals to a few

- Those few who love Twitter comprise an influential intellectual and cultural cohort, and at internet scale, even niches can be substantial in size

I’ve written before in Status as a Service or The Network’s the Thing about how Twitter hit upon some narrow product-market fit despite itself. It has never seemed to understand why it worked for some people or what it wanted to be, and how those two were related, if at all. But in a twist of fate that is often more of a factor in finding product-market fit than most like to admit, Twitter's indecisiveness protected it from itself. Social alchemy at some scale can be a mysterious thing. When you’re uncertain which knot is securing your body to the face of a mountain, it’s best not to start undoing any of them willy-nilly. Especially if, as I think was the case for Twitter, the knots were tied by someone else (in this case, the users of Twitter themselves).

But Elon Musk is not one to trust someone else’s knots. He’s made his fortune by disregarding other people’s work and rethinking things from first principles. To his credit, he’s worked miracles in categories most entrepreneurs would never dream of tackling, from electric cars to rockets to satellite internet service. There may be only a handful of people who could’ve pulled off Tesla and SpaceX, and maybe only one who could’ve done both. When the game is man versus nature, he’s an obvious choice. When it comes to man versus human nature, on the other hand…

This past year, for the first time, I could see the end of the road for Twitter. Not in an abstract way; I felt its decline. Don’t misunderstand me; Twitter will persist in a deteriorated state, perhaps indefinitely. However, it's already a pale shadow of what it was at its peak. The cool kids are no longer sitting over in bottle service knocking out banger tweets. Instead, the timeline is filled with more and more strangers the bouncer let in to shill their tweetstorms, many of them Twitter Verified accounts who paid the grand fee of $8 a month for the privilege. In the past year, so many random meetings I have with one-time Twitter junkies begin with a long sigh and then a question that is more lamentation than anything else: “How did Twitter get so bad?”

It’s sad, but it’s also a fascinating case study. The internet is still so young that it’s still momentous to see a social network of some scale and lifespan suddenly lose its vitality. The regime change to Elon and his brain trust and the drastic changes they’ve made constitute a natural experiment we don’t see often. Usually, social networks are killed off by something exogenous, usually another, newer social network. Twitter went out and bought Chekhov’s gun in the first act and use it to shoot itself in the foot in the third act. Zuckerberg can now extend his quip about Twitter being a clown car that fell into a gold mine.

In The Rise and Decline of Nations, Mancur Olson builds on his previous book The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups to discuss how and why groups form. What are the incentives that guide their behavior?

One of his key insights is what I think of as his theory of group inertia. Groups are hard to form in the first place. Think of how many random Discord communities you were invited into the past few years and how many are still active. “Organization for collective action takes a good deal of time to emerge” observes Olson.

However, inertia works both before and after product-market fit. Once a group has formed, it tends to persist even after the collective good it came together to provide is no longer needed.

The same is true of social networks. As anyone who has tried to start one knows, it’s not easy to jump-start a social graph. But if you manage by some miracle to conjure one from the void, and if you provide that group with a reasonable set of ways for everyone to hang out, network effects can keep the party going long after last call. The group inertia that is your enemy before you’ve coalesced a community is your friend after it’s formed. Anyone who’s ever hosted a party and provided booze knows it’s often hard to get the last stragglers to leave. We are a social species.

No social network epitomizes this more than Twitter. It’s not that Twitter was a group of users that assembled for the explicit goal of producing some collective good. Its rise was too emergent to fit into any such directed narrative. But the early years of inertial drag (for years it was literally inert, inertia and inert sharing the same etymological root) followed by later years of inertial momentum fit the broad arc of Olson’s group theory.

I revisit Olson and Twitter’s history because the specifics of how Twitter found product-market fit are critical to understanding its current dissolution. Social networks are path dependent. This is especially true in the West where social networks are largely ad-subsidized and where they’re almost all built around a singular dominant architecture of an infinite scrolling feed optimized for serving ads on a mobile phone. The path each network took to product-market fit selected for a specific user base. As with any community, but especially ones forced to cluster in close proximity in a singular feed, as is common in the West, the people making up the community go a long way towards determining its tenor and values. Its vibes. The composition of its users then determines how conducive that network is to what types of advertising and at what scale. Finally, closing the circle of life, those ad dynamics then influence the network’s middle age evolution as a service. Money may not begin the conversation, that starts with the users, but money gets the final word.

Of all the social networks that achieved some level of scale in this first era of social media, perhaps no other was tried and abandoned by as many users as Twitter. Except for the extremely online community in which I’m deeply embedded (and that I suspect many of my readers are a part of), most normal, well-adjusted humans churned out of Twitter long ago.One of the trickiest things about projecting off of early growth rates for startups in tech is that even fads can generate massive absolute numbers early on if marketed broadly to a global audience. Without looking at early retention and churn rates, you may extrapolate a much larger terminal user base size than will actually stick around. Think about eBay or Groupon, for example. This same caution needs to be applied to Threads; one of the central questions is whether Twitter reached all the people who enjoy microblogging or whether Meta has some magic formula that will allow it to scale to a much larger population. That’s not ideal from a business perspective, but the upside is that those who made it through that great filter selected hard into Twitter’s unique experience. Most sane people don’t enjoy seeing a bunch of random bursts of text from strangers one after the other, but those that do really really love it. And, despite Twitter’s notoriously slow rate of shipping new features over the years, it eventually offered just enough knobs and dials for its users to wrestle their timelines into a fever dream of cacophonous public discourse that hasn’t been replicated elsewhere. More than any other social network, Twitter was one its users seized control of and crafted into something workable for themselves. To its heaviest and most loyal users, it felt at times like a co-op. Recent events remind us it isn’t.

Out of a petri dish that was lifeless for years emerged a culture of creatives, trolls, humorists, politicians, and other public intellectuals screaming at each other in 140 and later 280-character bursts, with even more users quietly gawking from the sideline. This so-called new town square was a 24/7 nightclub for real-world introverts but textual extroverts. My tribe.

This was as entertaining a spectacle as it was shaky a business. Twitter ads have always been hilariously random, and it’s to the credit of the desirable demographics of many of its users that advertisers continued to stick around to have their brands paraded between sometimes questionable, often horrifyingly offensive tweets. But its poor economics as a business shielded it from direct competition. Even if you could recreate its nerdy gladiatorial vibe, why would you? For years it seemed Twitter might persist in this delicate equilibrium, a Galapagos tortoise sunning on an island all to itself, surrounded by ocean as far as the eye could see.

Back to Olson: “Selective incentives make indefinite survival feasible. Thus those organizations for collective action, at least for large groups, that can emerge often take a long time to emerge, but once established they usually survive until there is a social upheaval or some other form of violence or instability.”

Well, “violence and instability” finally came to Twitter in the form of Elon Musk’s ownership. In almost every way, his stewardship has been the polar opposite of the previous regime’s. Politically, to be sure. But more notably, whereas Twitter was previously known as a company that rarely shipped any substantial changes, new Twitter seemed for months to ship things before having thought them through or even QA’ing them. Random bugs seem to pop up in the app all the time, and changes were pushed out and then reversed within the day. Many a day this past year, Twitter has been the main character of the types of drama it used to serve as the forum to discuss.

In classic Twitter fashion, the irony is that it now seems to be in decline not from doing too little but from doing too much. It turns out the way to overcome Olson’s group inertia is to run in swinging a machete, cutting wires, firing people, unplugging computers, flipping switches, tweaking parameters, anything to upset an ecosystem hanging on by a delicate balance. It was, if nothing else, a fascinating natural experiment in how to nudge a network out of longstanding homeostasis.

Given that Musk ended up having to overpay for Twitter by upwards of 4X, thanks to Delaware Chancery Court, it’s not at all surprising he and his new brain trust might choose to take an active hand in trying to salvage as much of his purchase price as possible.

But this heavy-handed top-down management approach runs counter to how Twitter achieved its stable equilibrium. In this way, Musk’s reign at Twitter resembles one of James Scott’s authoritarian high modernist failures. Twitter may have seemed like an underachieving mess before, but its structure, built up piece by piece by users following, unfollowing, liking, muting, and blocking over years and years in a continuous dialogue with the feed algorithm? That structure had a deceptive but delicate stability. Twitter and its users had assembled a complex but functional community, Jane Jacobs style. Every piece of duct tape and every shim put there by a user had a purpose. It may have been Frankensteinian in its construction, but it was our little monster.

This democratic evolution has long been part of Twitter’s history. Many of Twitter’s primary innovations like hashtags, much of its terminology like the word tweets, seemed to come bottom-up from the community of users and developers. This may have capped its scalability; a lot of its syntax has always seemed obtuse (who can forget how you had to put a period before a username if it opened a tweet so that the network wouldn’t treat it as a reply and hide it in the timeline). But, conversely, the service seemed to mold itself around the users who stuck with its peculiar vernacular. After all, they were often the ones who came up with it.

Olson again:

Stable societies with unchanged boundaries tend to accumulate more collusions and organizations for collective action over time.

What established the boundaries of Twitter? Two things primarily. The topology of its graph, and the timeline algorithm. The two are so entwined you could consider them to be a single item. The algorithm determines how the nodes of that graph interact.

The machine learning algorithms have been crucial to scaling our largest social media feeds. They are among the most enormous social institutions in human history, but we don't often think of them that way. It's often remarked upon that Facebook is larger than any country or government, but it should be remarked upon more? I think it's so shocking and horrifying to so many people that they prefer to block it out of their mind. In a literal sense, Twitter has always just been whose tweets show up in your timeline and in what order.

In the modern world, machine learning algorithms that mediate who interacts with whom and how in social media feeds are, in essence, social institutions. When you change those algorithms you might as well be reconfiguring a city around a user while they sleep. And so, if you were to take control of such a community, with years of information accumulated inside its black box of an algorithm, the one thing you might recommend is not punching a hole in the side of that black box and inserting a grenade.

So of course that seems to have been what the new management team did. By pushing everyone towards paid subscriptions and kneecapping distribution for accounts who don’t pay, by switching a TikTok style algorithm, new Twitter has redrawn the once stable “borders” of Twitter’s communities.

This new pay-to-play scheme may not have altered the lattice of the Twitter graph, but it has changed how the graph is interpreted. There’s little difference. My For You feed shows me less from people I follow, so my effective Twitter graph is diverging further and further from my literal graph. Each of us sits at the center of our Twitter graph like a spider in its web built out of follows and likes, with some empty space made of blocks and mutes. We can sense when the algorithm changes. Something changed. The web feels deadened.

I’ve never cared much about the presence or not of a blue check by a user’s name, but I do notice when tweets from people I follow make up a smaller and smaller percentage of my feed. It’s as if neighbors of years moved out from my block overnight, replaced by strangers who all came knocking on my front door carrying not a casserole but a tweetstorm about how to tune my ChatGPT and MidJourney prompts.

I tried switching to the Following from the For You feed, but it seems the Following feed is strictly reverse chronological. This is a serious regression to the early days of Twitter when you had to check your feed frequently to hope to catch a good tweet from any single person you followed. We tried this before; it was terrible then, it’s terrible now.

This weakening of the follow works in the other direction, too. Many people who follow me tell me they don’t see as many of my tweets as they used to. All my followers are accumulated social capital that seem to have been rendered near worthless by algorithmic deflation.

With every social network, one of the most important questions is how much information the structure of the graph itself contains. Because Twitter allows one-way following, its graph has always skewed towards expressing at least something about the interests of its users. Unlike on Facebook, I didn’t blindly follow people I knew on Twitter. The Twitter graph, more than most, is an interest graph assembled from a bunch of social graphs standing on each other’s shoulders wearing an interest graph costume. Not perfect, but not nothing.

The new Twitter algorithm tossed that out.

If you’re going to devalue the Twitter graph’s core primitive, the act of following someone, you’d better replace it with something great. The name of the new algorithmic feed hints at what they tried: For You. It’s nomenclature borrowed from TikTok, the entertainment sensation of the past few years.

I’ve written tens of thousands of words on TikTok in recent years (my three essays on TikTok are here, here, and here), and I won’t rehash it all here. What prompted my fascination with the app was that it attacked the Western social media incumbents at an oblique angle. In TikTok and the Sorting Hat, I wrote:

The idea of using a social graph to build out an interest-based network has always been a sort of approximation, a hack. You follow some people in an app, and it serves you some subset of the content from those people under the assumption that you’ll find much of what they post of interest to you. It worked in college for Facebook because a bunch of hormonal college students are really interested in each other. It worked in Twitter, eventually, though it took a while. Twitter's unidirectional follow graph allowed people to pick and choose who to follow with more flexibility than Facebook's initial bi-directional friend model, but Twitter didn't provide enough feedback mechanisms early on to help train its users on what to tweet. The early days were filled with a lot of status updates of the variety people cite when criticizing social media: "nobody cares what you ate for lunch."

But what if there was a way to build an interest graph for you without you having to follow anyone? What if you could skip the long and painstaking intermediate step of assembling a social graph and just jump directly to the interest graph? And what if that could be done really quickly and cheaply at scale, across millions of users? And what if the algorithm that pulled this off could also adjust to your evolving tastes in near real-time, without you having to actively tune it?

The problem with approximating an interest graph with a social graph is that social graphs have negative network effects that kick in at scale. Take a social network like Twitter: the one-way follow graph structure is well-suited to interest graph construction, but the problem is that you’re rarely interested in everything from any single person you follow. You may enjoy Gruber’s thoughts on Apple but not his Yankees tweets. Or my tweets on tech but not on film. And so on. You can try to use Twitter Lists, or mute or block certain people or topics, but it’s all a big hassle that few have the energy or will to tackle.

This is more commonly accepted now, but back in 2020 when I wrote this piece, TikTok’s success was still viewed with a lot of skepticism and puzzlement. Since then, we’ve seen Instagram and Twitter both try emulating TikTok’s strategy. Both Instagram and Twitter now serve much less content from people you follow and more posts selected by machine learning algorithms trying to guess your interests.

Instagram has been more successful in part because it has formats like Stories that keep content from one’s follows prominent in the interface. There’s social capital of value embodied in the follow graph, and arguably it’s easier for Instagram to preserve much of that while copying TikTok than it is for TikTok to build a social graph like Instagram.

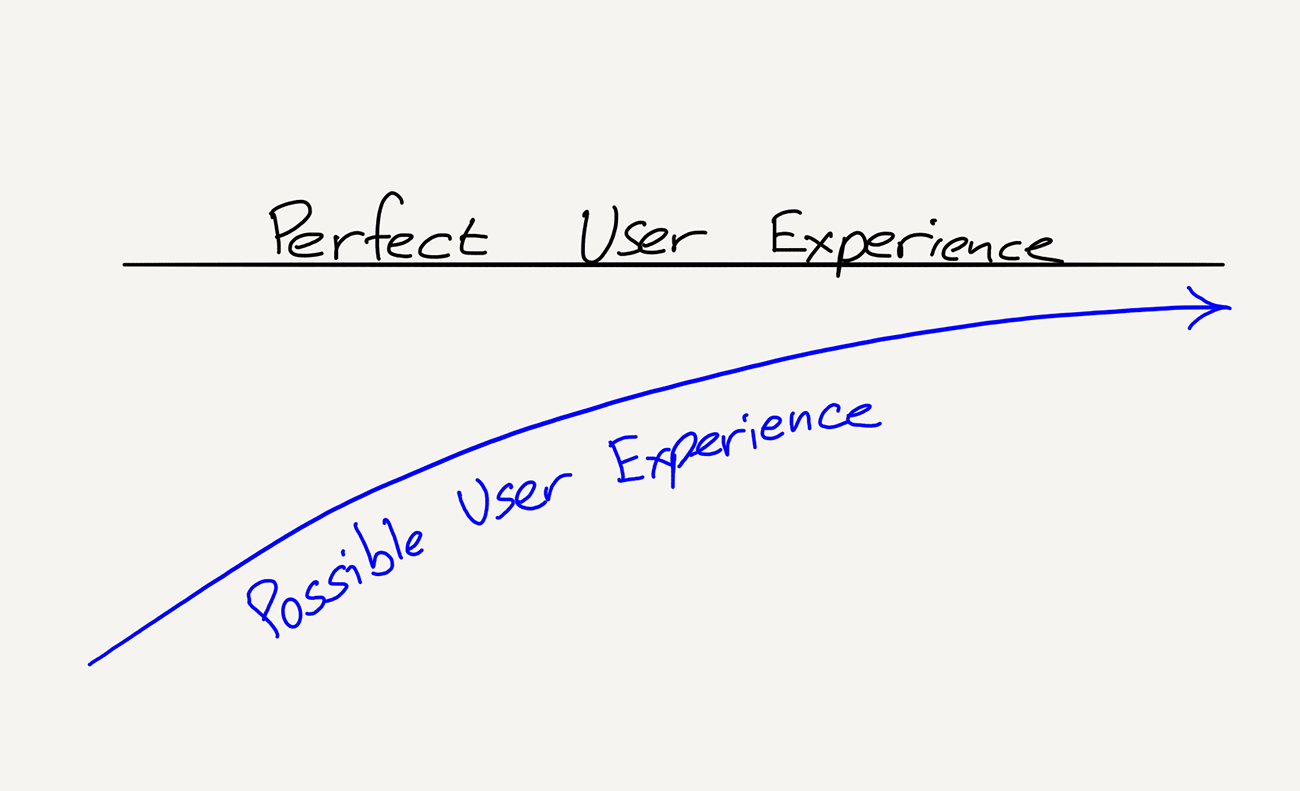

But that’s a topic for another day. Twitter is the app on trial today. And of all Twitter’s recent missteps, I think this was the most serious unforced error. For a variety of design reasons, Twitter will likely never be as accurate an interest graph as, say, TikTok is an entertainment network.

As I’ve written about before in Seeing Like An Algorithm, Twitter’s interface doesn’t capture sentiment, both positive and negative, as cleanly, as TikTok.

Let’s start with positive sentiment. On this front, Twitter is…fine? It’s not for lack of usage. I’ve used Twitter a ton over more than a decade now, I’ve followed and unfollowed thousands of accounts, liked even more tweets, and posted plenty of tweets and links. I suspect one issue is that many tweets don’t contain enough context to be accurately classified automatically. How would you classify a tweet by Dril?

But perhaps even more damning for Twitter is its inability to see negative sentiment. Allowing users to pay for better tweet distribution leaves the network vulnerable to adverse selection. That’s why the ability to capture negative sentiment, especially passive negative sentiment, is so important to preserving a floor of quality for the Timeline.

Unfortunately, capturing that passive disapproval is something Twitter has never done well. In Seeing Like an Algorithm, I wrote about how critical it was for a service’s design to help machine learning algorithms “see” the necessary feedback from users, both positive and negative. That essay’s title was inspired by Scott’s Seeing Like a State which described how high modernist governments depended on systems of imposed legibility for a particular authoritarian style of governance.

Modern social networks lean heavily on machine learning algorithms to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise in feeds. To manually manage complex adaptive systems at the scale of modern social media networks would be impossible otherwise. One of the critiques of authoritarian technocracies is that they quickly lose touch with the people they rule over. It's no surprise that such governments have also looked at machine learning algorithms paired with the surveillance breadth of the internet as a potential silver bullet to allow them to scale their governance. The two entities that most epitomize each of these both come out of China: Bytedance and the CCP. The latter, in particular, has long been obsessed with cybernetics, despite having followed it down a disastrous policy rabbit hole before.

But these cybernetic systems, in the Norbert Wiener sense, only work well if their algorithms see enough user sentiment and see it accurately. Just as Scott felt high modernism failed again and again because those systems overly simplified complex realities, Twitter’s algorithm operates with serious blind spots. Since every output is an input in a cybernetic system, failure to capture all necessary inputs leads to noise in the timeline.

Twitter doesn’t see a lot of passive negative sentiment; it’s a structural blind spot. In a continuous scrolling interface with multiple tweets on screen at any one time, it’s hard to tell disapproval from apathy or even mild approval because the user will just scroll past a tweet for any number of reasons.

This leads to a For You page that feels like it’s missing my friends and awkwardly misinterpreting my interests. Would you like yet another tweetstorm on AI and how it can change your life? No, well too bad, have another. And another. For someone who claims to be worried about the dangers of AI, Elon’s new platform sure seems to be pushing us to play with it.

In the rush to copy TikTok, many Western social networks have misread how easy it is to apply lessons of a very particular short video experience to social feeds built around other formats. If you’re Instagram Reels and your format and interface are a near carbon copy, then sure, applying the lessons of my three TikTok essays is straightforward. But if you’re Twitter, a continuous scrolling feed of short textual content, you’re dealing with a different beast entirely.

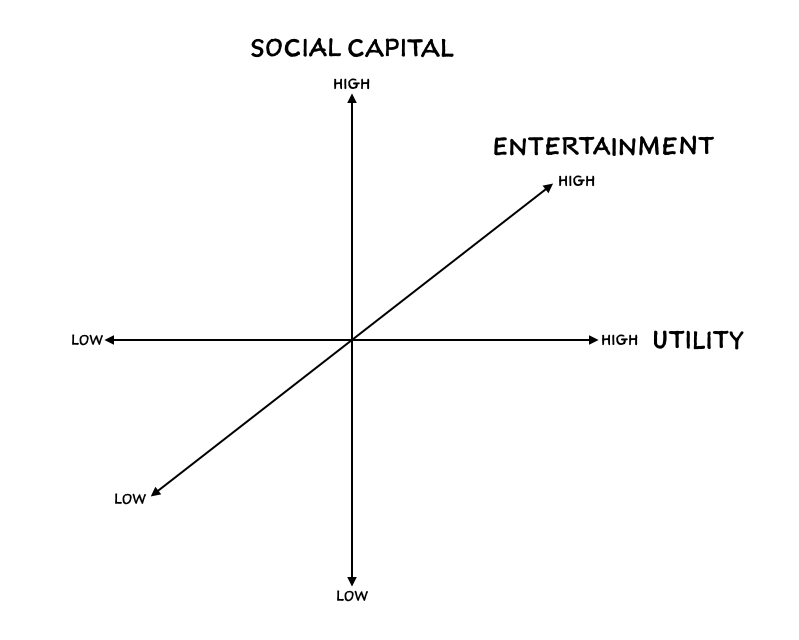

Even TikTok sometimes seems to misunderstand that its strength is its purity of function as an interest/entertainment graph. Its attempts to graft a social graph onto that have struggled because social networking is a different problem space entirely. Pushing me to follow my friends on TikTok muddies what is otherwise a very clear product proposition. Social networking is a complex global maximum to solve for. In contrast, entertaining millions of people with an individual channel personalized to each of them is an agglomeration of millions of local maximums. TikTok’s interface paired with ByteDance’s machine learning algorithms are perfect for solving the latter but much less well-suited towards social networking.

Here’s another way to think about it. The difference between Twitter and an algorithmic entertainment network like TikTok is that you could fairly quickly reconstitute TikTok even without its current graph because its graph is a much less critical input to its algorithm than the user reactions to any random sequence of videos they’re served.

If Twitter had to start over without its graph, on the other hand, it would be dead (which speaks to why Twitter clones like BlueSky which are just Twitter minus the graph and with the same clunky onboarding process seem destined for failure). The new For You feed gives us a partial taste of what that might look like, and it's not pretty.

I ran a report recently on all the accounts I follow on Twitter. I hadn’t realized how many of them had been dormant for months now. Many were people whose tweets used to draw me to the timeline regularly. I hesitate to unfollow them; perhaps they’ll return? But I’m fooling myself. They won’t. Inertia again. A user at rest tends to stay at rest, and a user that flees tends to be gone for good.

Even worse, many accounts I follow look to have continued to tweet regularly over the past year. I just don’t see their tweets anymore. The changes to the Twitter algorithm bulldozed over a decade’s worth of Chesterton fences in a few months.

The other prominent mistake of the Elon era is more commonly cited, and I tend to think it’s overrated, but it certainly didn’t help. It’s the type of mistake only a prominent and polarizing figure running a social network could stumble into: his own participation on the platform he owns. The temptation is understandable. If you overpaid for a social network by tens of billions of dollars, why shouldn’t you be able to use it as you please? Why not boost your own tweets and use it as a personal megaphone? Why buy a McLaren if you take it for a spin and total it? He declared that one of his reasons for purchasing Twitter was to restore it to being a free speech platform, so why not speak his mind?

More than any tech CEO, he’s become a purity test for one’s technological optimism. His acolytes will follow him, perhaps even literally, to Mars, while his critics consider him the epitome of amoral Silicon Valley hubris. That he is discussed in such simplistic, binary terms is ironic; it exemplifies the nature of discourse on Twitter. It’s no surprise that many Twitter alternatives market themselves simply as Twitter minus Elon (though I suspect most people just want, like me, a Twitter with the same graph but minus the new For You algorithm).

But there’s a Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle of social in play here. Every tweet of his alters the fabric of Twitter so drastically that it’s almost impossible for some users to coexist on Twitter alongside him. He singlehandedly brought some users back to Twitter and sent others fleeing for the exits. There are no neutral platforms, as many have noted, but Musk’s gravitational field has warped Twitter’s entire conversational orbit and brand trajectory. Leaving Twitter, or simply refusing to pay for verification, is now treated as an act of resistance. It’s debatable whether that’s fair, but reality doesn’t give a damn.

Some users might have stuck around had Musk used his Twitter account solely for business pronouncements, but that wouldn’t be any fun now would it? He’s always enjoyed trolling his most vocal critics on Twitter, but it hits different when he’s the owner of said platform used by millions of cultural elites the world over.

Earlier this year, it appeared that Musk had comped Twitter Verified blue checkmarks to prominent public figures like Stephen King, some of whom had repeatedly criticized him. This led to the absurd and prolonged spectacle of dozens of famous people asserting over and over that they had absolutely not paid the meager sum of $8 a month for the scarlet, err, baby blue checkmark that now adorned their profiles, not to be confused with the blue checkmark that formerly appeared in the same spot that they hadn’t paid for. This made the blue checkmark a sort of Veblen good; more people seemed to want one when you couldn’t buy one, when it was literally priceless.The price is an odd one. $8 a month is not expensive enough to be a wealth signal, but it’s enough to feel like an insult to users who feel like they subsidized the popularity of Twitter over the years with their pro bono wit. I believe it was Groucho Marx who once said something to the effect of not wanting to belong to any club that would accept him as a member for the tidy sum of $8 a month.

This culminated in one weekend when Musk engaged in a protracted back and forth with Twitter celebrity shitposter Dril, pinning a Twitter Blue badge on his profile over and over only to have Dril remove it by changing his profile description. This went on for hours, and some of us followed along, like kids on the playground watching a schoolboy chase a girl holding a frog. This was bad juju and everyone knew it.

I’ll miss old Twitter. Even now, in its diminished state, there isn’t any real substitute for the experience of Twitter at its peak. Compared to its larger peers in the social media space, Twitter always reminded me of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s late-night speech as Lester Bangs in Almost Famous, delivered over the phone to the Cameron Crowe stand-in William Miller, warning him about having gotten seduced by Stillwater, the band Miller was profiling for The Rolling Stone:

Oh man, you made friends with them. See, friendship is the booze they feed you. They want you to get drunk on feeling like you belong. Because they make you feel cool, and hey, I met you. You are not cool. We are uncool. Women will always be a problem for guys like us, most of the great art in the world is about that very problem. Good-looking people they got no spine, their art never lasts. They get the girls but we’re smarter. Great art is about guilt and longing. Love disguised as sex and sex disguised as love. Let’s face it, you got a big head start. I’m always home, I’m uncool.

The only true currency in this bankrupt world is what you share with someone else when you’re uncool. My advice to you: I know you think these guys are your friends. You want to be a true friend to them? Be honest and unmerciful.

In the world of Almost Famous, Instagram would be the social network for the Stillwaters, the Russell Hammonds, the Penny Lanes. Beautiful people, cool people. Twitter was for the uncool, the geeks, the wonks, the wits, the misfits. Twitter was honest and unmerciful, sometimes cruelly so, but at its best it felt like a true friend.

It was striking how many of Elon’s early tweets about Twitter’s issues seemed to pin Twitter’s underperformance on engineering problems. Response times, things of that nature. But Twitter’s appeal was never a pure feat of engineering, nor were its problems solely the fault of engineering malpractice. They were human in nature. Twitter isn’t, as many have noted, rocket science, making it a particularly tricky domain for a CEO of, among other things, a rocket company. Ironically, Norbert Wiener, often credited as the father of cybernetics, a field which has lots of relevance to analyzing social networks, worked on anti-aircraft weapons during World War II. So if you really want to nitpick, your vast conspiracy board might somehow connect running a social network to rocket science. You can test unmanned rockets, and if they blow up on take-off or re-entry, you’ve learned something, no harm done. But running the same test on a social media service is like testing rockets with your users as passengers. Crash a rocket and those users aren’t going to be around for the next test flight.

It’s not clear there will ever be a Twitter replacement. If there is one, it won’t be the same. It may look the same, but it will be something else. The internet is different now, and the conditions that allowed Twitter to emerge in the first place no longer exist. The Twitter diaspora has scattered to all sorts of subscale clones or alternatives, with no signs of agreeing on where to settle. As noted social analyst Taylor Swift said, “We are never ever getting back together.”

For this reason, Twitter won’t ever fully vanish unless management pulls the plug. None of the contenders to replace Twitter has come close to replicating its vibe of professional and amateur intellectuals and jesters engaged in verbal jousting in a public global tavern, even as most have lifted its interface almost verbatim. Social networks aren’t just the interface, or the algorithm, they’re also about the people in them. When I wrote “The Network’s the Thing” I meant it; the graph is inextricable from the identity of a social media service. Change the inputs of such a system and you change the system itself.

Thus Twitter will drift along, some portion of its remaining users hanging out of misguided hope, others bending the knee to the whims of the new algorithm.

But peak Twitter? That’s an artifact of history now. That golden era of Twitter will always be this collective hallucination we look back on with increasing nostalgia, like alumni of some cult. With the benefit of time, we’ll appreciate how unique it was while forgetting its most toxic dynamics. Twitter was the closest we’ve come to bottling oral culture in written form.

Media theorist Harold Innis distinguished between time-biased and space-biased media:

The concepts of time and space reflect the significance of media to civilization. Media that emphasize time are those durable in character such as parchment, clay and stone. The heavy materials are suited to the development of architecture and sculpture. Media that emphasize space are apt to be less durable and light in character such as papyrus and paper. The latter are suited to wide areas in administration and trade. The conquest of Egypt by Rome gave access to supplies of papyrus, which became the basis of a large administrative empire. Materials that emphasize time favour decentralization and hierarchical types of institutions, while those that emphasize space favour centralization and systems of government less hierarchical in character.

Twitter always intrigued me because it has elements of both. It always felt like it compressed space—the timeline felt like a single lunch room hosting a series of conversations we were all participating in or eavesdropping on—and time—every tweet seemed to be uttered to us in the moment, and so much of it was about things occurring in the world at that moment (one of the challenges of machine learning applied to news and Tweets both is how much of it has such a short half-life versus the more evergreen nature of TikToks, YouTube videos, movies, and music. A lot of Twitter was textual, but the character limit and the ease of replying lent much of it an oral texture. It felt like a live, singular conversation.

When reviewing a draft of this piece, my friend Tianyu wrote the following comment, which I’ll just cite verbatim, it’s so good:

Twitter feels like a perfect example of what James W. Carey calls the "ritual view of communication" (see Communication as Culture). Its virality doesn't come from transmission alone, but rather the quasi-religiosity of it; scrolling Twitter while sitting on the toilet is like attending a mass every Sunday morning. Like religions, Twitter formulates participatory rituals that come with a public culture of commonality and communitarianism. These rituals are then taken for granted—they become how people on the internet consume information and interact with one another by default.

Religious rituals rise and fall. Today all major religions have, at some point, become a global mimesis through missionary work, political power, and imperial expansions. Musk's regime is basically saying, 'oh well, Christianity isn't expanding fast enough. What we need to do is to rewrite the Bible and abolish the clergy. That'll do the work.'

Carey often notes that communication shares the same roots as words like common, community, and communion. Combine the ritualistic nature of Twitter with its sense of compressing space and time and you understand why its experience was such a convincing illusion of a single global conversation. I suspect Carey would argue that the simulacrum of such a conversation effectively created and maintained a community.

Even the vocabulary used to describe Twitter reinforced its ritualistic nature. Who would be today’s main character, we’d ask, as if that day’s Twitter drama was a single narrative we were all reading. We’d go to see the list of Trending Topics for the day as if looking to see who was being tarred and feathered in the Twitter town square that day. There was always a mob to join if you wanted to cast a stone, or a meme template of the day to borrow.

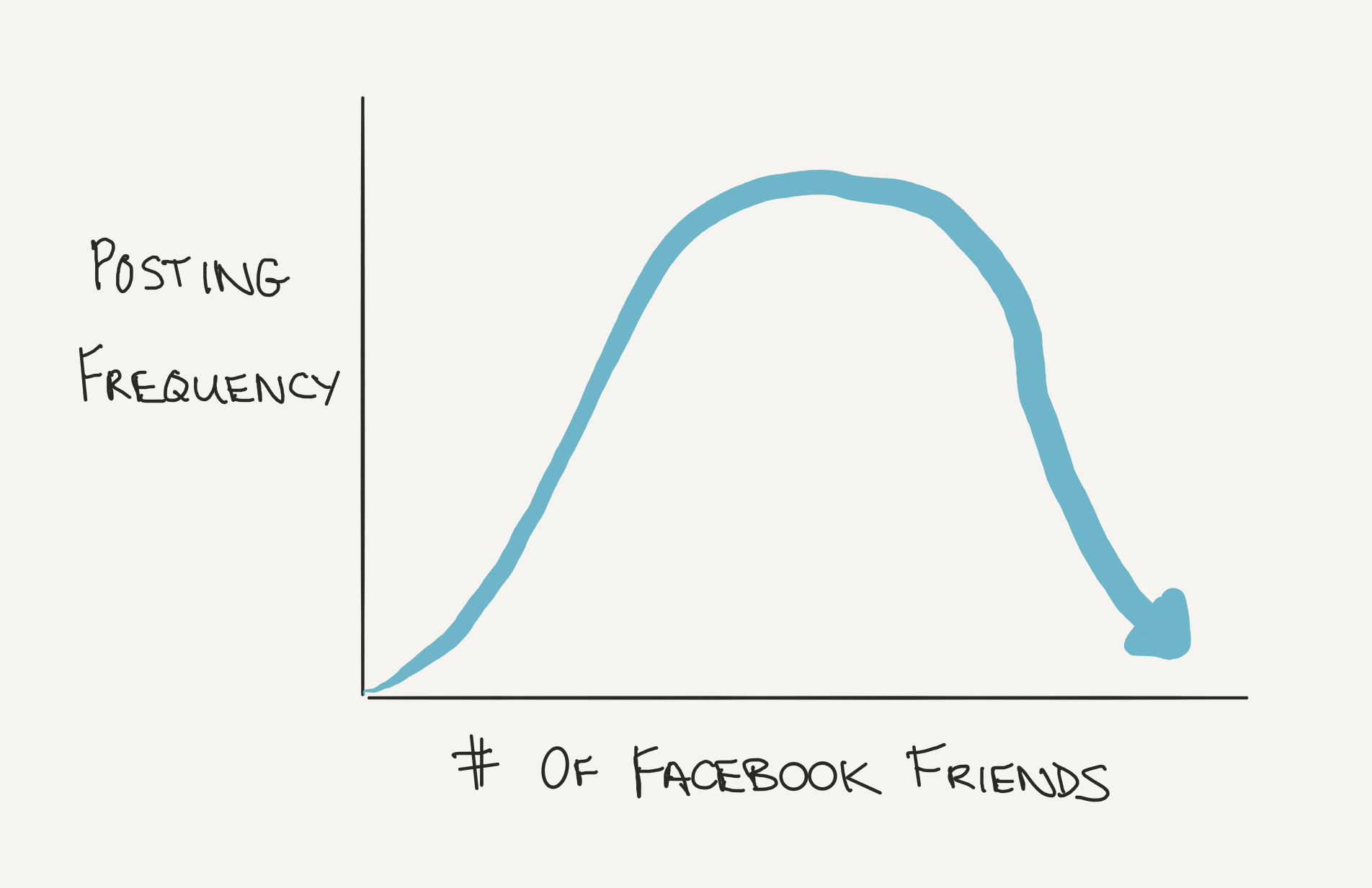

Friends would forward me tweets, and at some point I stopped replying “Oh yeah I saw that one already” because we had all seen all of them already. Twitter was small, but more importantly, it felt small. Users often write about how Twitter felt worse once they exceeded some number of followers, and while there are obvious structural reasons why mass distribution can be unpleasant, one underrated drawback of a mass following was the loss of that sense of speaking to a group of people you mostly knew, if not personally, then through their tweets.

In a way, Twitter’s core problem is so different than that of something like TikTok, which, as I noted earlier, is a challenge of creating a local maximum for each user. Twitter at its best felt, like Tianyu described it to me, a global optimum. In reality, it’s never so binary. Even in a world of deep personalization, we want shared entertainment and grand myths, and vice versa. TikTok has its globally popular trends and Twitter its micro-communities. But a TikTok-like algorithm was always going to be particularly susceptible to ruining the cozy, communal feel of a scaled niche like Twitter.

I’ve met more friends in the internet era through Twitter than any other social media app. Some of my closest friends today first entered my life by sliding into my DM’s, and it saddens me to see the place emptying out.

All of this past year, as a slow but steady flow of Twitter’s more interesting users has made their way to the exits, unwilling to fight to be heard anymore, or just stopped tweeting, I’ve still opened the app daily out of habit, and to research for pieces like this. But the vibes are all off. I haven’t churned yet, but at the very least, I’ve asked the bartender to close out my tab.

If Twitter’s journey epitomizes the sentimental truism that the real treasure was the friends we made along the way, then the story of its demise will begin the moment we could no longer find those friends on that darkened timeline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: Thanks to my friends Li and Tianyu for reading drafts of this piece at various stages and offering such rapid feedback. Considering the length of my pieces, that's no small thing. Their encouragement and useful notes and questions helped me refine and clarify my thinking. Also, if it wasn’t for Twitter, I probably wouldn’t know either of them today.

Inspiration for the title of this post comes from this which is based on this.

As my own Twitter usage fades, I plan to ramp back up writing on my website. If you're interested in keeping up, follow my Substack which I plan to spin back up to keep folks updated on my latest writing and where I’ll drop, among other things, a follow-up to this piece with my thoughts on Threads.